Acting Assistant Adjutant-General.

Copied from The Official Records of the War of Rebellion.

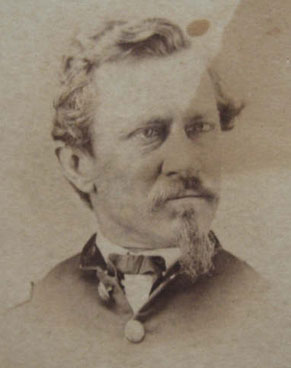

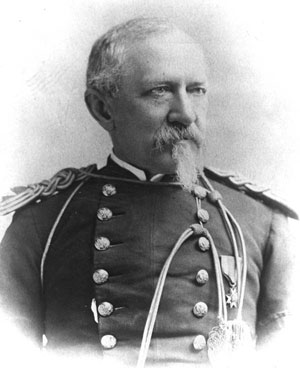

Letters from Captain Langdon after the battle

Editor's Note: Captain Loomis L. Langdon fought against the Seminole Indians before the Civil War. During the War he made sketches and subsequently studied painting at the National Portrait Gallery in London, England. However, he also stayed in the U.S. Army after the War and rose to high rank. While serviing as Chief of Artillery, XXV Corps, Army of the James, Captain Langdon assisted Lieutenant Johnston de Peyster (Wikipedia site) in raising the first American flag over Richmond, the just captured capital of the Confederacy, on April 3, 1865.

Other Reports from Olustee

Battle of Olustee home page

http://battleofolustee.org/