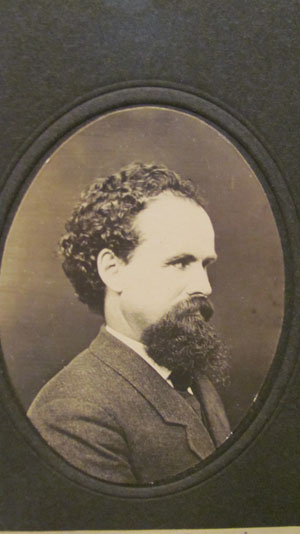

Post-war photograph.

Born in England, but residing in Concord, New Hampshire, Robert Farrand

enlisted on 29 October 1861 as a corporal. He was wounded at Fort Wagner

on 18 July 1863 and was promoted to sergeant on 28 November 1863. Like

his brother, Robert was also wounded and captured at the Battle of Olustee.

He was released from captivity on 30 November 1864 as he was totally

blind from his wounds. He was discharged on 23 June 1865.

Carte de Visite from the Richard Ferry Collection. Used with permission.

The following is taken from the History of the 7th Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers:

Sergt. Robert O. Farrand was born in Dunkinfield, England, and was a resident of Fisherville (now Penacook) at the breaking out of the War of the Rebellion, and at the age of twenty-one enlisted, October 29, 1861, as a private in Company E, Seventh N. H. Volunteers, and was appointed corporal and mustered in as such when his company was mustered into the United States service, November 7, 1861. He was wounded July 18, 1863, in the assault on Fort Wagner, S. C. ; was promoted to sergeant November 28, 1863 ; and was severely wounded and captured at the battle of Olustee, Fla., February 20, 1864, his wound resulting in total blindness the moment it was received. Later he was paroled and exchanged, and was discharged from the service, to date June 23, 1865.

He will be more readily remembered by the original members of the regiment from the fact that with Sergt. Cyrus Bidwell, of the same company (they were both corporals at that time), he performed the duty of marker for the regiment on all drills, etc.

His prison experiences covered many months, and as related by him will be found quite interesting :

"On the morning of February 20, 1864, the forces under the command of General Seymour, which were stationed at Barbour's Plantation, Fla., of which my regiment was a part, was ordered forward towards Lake City, about thirty miles away. Everything about the march for the first fifteen miles was as pleasant as could be desired, but what a change was to come over the spirit of our dreams. We halted for rest and to eat our lunch. Soon shots were heard on the picket line: every old soldier will know what this meant, and that some of us, who for more than two years had marched shoulder to shoulder would, before the setting of the sun on that day, sleep the sleep that knows no waking. Many others would be maimed for life — who would it be? All hoped they would come out of the approaching conflict safe. It was a vain hope. Soon an orderly came riding at full speed from the front with orders for one battalion of the Seventh Conn. Volunteers, under Colonel Hawley, to march to the front on the double-quick. Shortly another order came for the whole force to move forward, and soon the battlefield of Olustee was reached. I do not intend to describe the battle, only to say my regiment entered the field left in front, and were marching by the flank; soon the order was given by Colonel Abbott to break into column of companies, followed shortly by an order to deploy on the eighth company. While executing this order. Acting Brigadier-General Hawley, of Connecticut, rode up to the rear of the regiment and ordered us to deploy on the second company, which so mixed the regiment up that it was obliged to go to the rear to reform. Soon after the regiment broke, the order was given by Colonel Abbott to cease firing. One soldier who was about to disobey the order attracted the attention of the writer, who turned his head to see if the soldier was going to fire and thus disobey orders. As I turned my head I saw Colonel Abbott and Colonel Hawley sitting on their horses talking together—that was the last I ever saw, for at that moment a buck-shot from the enemy struck me in the left temple, passed back of both eyes, severing the optic nerve in both eyes, and lodged back of the right eye, where it still remains, totally destroying the sight of both eyes. I instantly became unconscious, in which condition I remained during the entire battle. When consciousness returned, I found myself lying on my face. The rebels were firing off the muskets they had found on the field. One of the shots from these muskets struck my knapsack on the right side, but didn't go through. Another struck the heel of my left boot, glanced up, and wounded me in the fleshy part of the thigh. As the firing ceased, I arose upon my knees, when I heard someone coming towards me. I hailed them, and asked them to take me to the hospital or to a fire, as I was cold, and was wounded, but could not tell how, as I felt no pain from my wound about the head, but was totally blind. He said there was no hospital near, so he would take me to a fire, which he did, and after making me as comfortable as he could he left me. Before he left me I ascertained that our forces had been defeated, and that I was a prisoner of war. He had been gone but a few minutes when I fainted from loss of blood. When I became conscious again I was not alone, several rebel soldier's were there; when they saw me move, they told me to take off my pants and give to them: that I declined to do, telling them that I was blind, and could not see to get any more. They said that if I did not take them off they w^ould cut my throat and take them. I told them that I hoped they would not do that, as I hoped to have a good deal of use for my throat in the future: I told them the pants were not worth the trouble, as they were a very old pair. After examining them they went away, leaving me once more alone. How long I remained so I could not tell, probably one or two hours. When I heard some teams going by, I hailed them, but the first gave no heed to me; the second stopped and picked me up and carried me to Olustee Station, about a mile and a half from the battletield. I remember being lifted out of the wagon and walking about six feet, which was the last thing I remembered, for my wounds bled so that I again fainted away, and remained in that condition for three days. When I once more returned to consciousness, I found myself in a stable in Lake City, fifteen miles from Olustee, where I got out of a wagon. Some of my comrades were with me, but I knew but little of what was taking place around me.

"When I did recover sufficiently to realize my condition, I learned that a rebel surgeon had examined me, but said I was not wounded, and must have been blinded by the bursting of a shell, saying the powder must have burned my eyes. In searching for my wound, he not so much as washed the blood from my face, and of course my wounds had not been dressed at all up to this time. I now began to feel the need of a good wash, and as there was no way to get one in the stable, I asked one of the colored waiters if he knew where Elizabeth Gould lived; he said he did, and I asked him to take me to her home. She, with many

others who were in Lake City, had lived in St. Augustine when the Seventh New Hampshire garrisoned that place; and as our regiment treated them kindly, they felt well disposed towards any of our regiment, and came to the hospital to see us—but to go back. The waiter started with me for Miss Gould's, but on the way saw Comrade Charles Danforth in a house, so took me in there. As we entered the house without knocking, Danforth and the lady met us, when Danforth asked me what was wanted. I told him where I was going, for what purpose, and we had come there by mistake. The lady invited me in, told the waiter to leave me there, she would see that I had the opportunity to wash and fix myself up. She took me into the dining-room, and after handing me a chair left me.

"She soon returned with hot water, towels, soap, and sponge, and proceeded to wash the blood from my face. When she applied the hot water and the blood was

removed, the wound opened, and she exclaimed, 'there is where you are wounded.' I immediately put my finger in the mouth of the wound to see how bad it was, and found that the ball that did the mischief must have been a buckshot about five-sixteenths of an inch in diameter. I had not, up to this time, sutfered any pain trom the wound, neither did I at any future time. After I finished my toilet, she brought me some food, consisting of biscuit, johnny cake, butter, and tea. This was the first food I had any remembrance of eating since I was taken prisoner.

"After I had eaten, she took me into the sitting-room, spread a blanket on the floor in front of the fireplace, and remarked, as she left the room, that I could lie down and get some rest. I, with some other wounded soldiers, remained there that night. I found that the lady of the house was a Union woman and was doing all she could to help the boys in blue. I remained in Lake City several days longer, and my wound was not dressed up to this time by any surgeon, nor indeed at any future time, and I was obliged to take the entire care of it myself. About the 4th of March, I, with others, was sent to

Tallahasse, the capital of the State. Here we had better quarters, being put into a church that had been used by colored people. We received kind treatment and the food was good, but coarse and scanty. To illustrate this, I bought five dollars' worth of food at a baker's, and though I had eaten breakfast only half an hour before, and then ate all the rebels would give me, I ate the whole five dollars' worth of baker's food, except one piece of gingerbread

about four inches square, and my stomach did not feel any trouble by the extra food. Another time I paid two dollars and fifty cents for a meal which consisted of two biscuits, two pieces of hoe-cake, two eggs, and several pieces of bacon about the size of a silver dollar. This was the cheapest meal I had while a prisoner. The money I bought this food with, I got by selling my gold pen with a silver holder for thirtv-five dollars. I should have said

before this that while lying unconscious on the battlefield, the rebels stole everything I had in my pockets except this pen, which thev did not find, as it was in my vest pocket. They even took the shoes from my feet, so the rest of the time I had to go barefooted. As I have said, our quarters were much better than they were at Lake City but our liberty was restricted. We were not allowed to go but a few rods from the building without permission, and even then a guard had to go with us. It was here that I heard that my brother Joseph was dead. I had heard that he was wounded, but did not know how badly. I felt sorry that I had not been able to see him, as I was but a short distance from where he died. As I said, I had to dress my wound myself: in order to get the matter out of the wound, I had to press on the eye. About a week after I arrived at Tallahassee, as I was engaged in dressing the wound, and while pressing on the eye, the ball of the eye burst, but it was three days before it entirely run out.

"The rebels now began to tell us that their government was building some nice hospitals at Americus, in Georgia, where we could be more comfortable than we were, and that we should have good beds to lie on. About a week later, they told us that the hospitals were all ready, and on the morning of Saturday, March 19, we bade adieu to Tallahassee, and with food enough to last us two days, we started for Georgia. Our first stop was at Chattahooche,

which place we reached in the afternoon. We were put into an old arsenal and kept until Sunday night. Then we were put on board a steamboat and sent up the Chattahoodie River to Fort Gains Landing. Alter leaving the steamer, we had to climb one hundred and ten steps to reach the height of land, then go about four hundred feet to the depot, where we expected cars to take us to Americus. But no cars were there, so we had to wait. It was a drizzly, rainy day, and the weather was cold, so the guards built a fire and we managed to keep warm. My comrade had to help me from the landing to the depot. I was so weak I was obliged to lie on the platform nearly all day, going every little while to the fire to get warm. My stay at the fire was short, as I could not stand but a few minutes without fainting away. Our food lasted only till Sunday night, so that Monday morning we had no breakfast. The officer in charge of the guard went to Fort Gains to get us something to eat, but they refused to issue any rations for us, and it looked as though we would have to go hungry for a while. In the afternoon I heard someone speak of a house about a half-mile away, and I asked the officer if he would send a guard with some of the men to

see if they could buy some corn bread. He consented, so I gave them ten dollars, all I had left from the sale of my pen. They were gone some time, but when they returned brought ten dollars' worth of corn-pones, which we divided among the prisoners. It was not more than half a meal for us, but much better than nothing.

"In the evening, a box car was run down to the depot, into which we were put for safe keeping for the night. There were twentty-two of us. The car door was closed within two inches and securely fastened. The bottom of the car was covered to the depth of half an inch with wet mud, in which we were compelled to sit or lie as we thought best. In the morning, our car was attached to a train, and we started for our destination. The people all along the line seemed to be expecting us, for at every depot crowds were gathered to get a sight of the 'Yanks.'

"About noon we reached Americus. Here we found that the story of the hospital and nice beds was a lie, told to us for what purpose we did not know. About 2 o'clock in the afternoon of this day, March 22, we reached Andersonville. After leaving the cars, we were marched to the stockade, about three quarters of a mile away, and, though we did not know it, what we had passed through was like paradise compared to what we afterwards suffered. Of the twenty-two men who entered Andersonville with me, only two, Charles Danforth, of Hopkinton, and myself, ever left it alive. England has never outlived the stigma of the 'Black hole of Calcutta,' and the Southern States will never outlive the stigma of Andersonville and other kindred prison pens.

"When we entered the stockade we were placed in different companies, to till up the ranks depleted by death. I was very fortunate in being assigned to a company which already contained fifteen men from my regiment. This was very pleasant, for I felt that, although I was blind, I was among friends who would assist me as far as they were able. At this time there were only about six thousand prisoners in the stockade, but the number was afterwards increased to about thirty-five thousand. For convenience in issuing rations, the prisoners were divided into detachments of two hundred and seventy each; each detachment was divided into three companies of ninety each, and each company was divided into four squads. These detachments, companies, and squads, were each in charge of a man from their own ranks. The manner of distributing the rations I will now describe: They were brought into the stockade in two-horse wagons, and each commander of a detachment was given the rations for two hundred and seventy men; these rations were divided into three equal parts, and that there might be no cause for complaint, one man would turn and look the other way, while the man in charge would place his hand on one of

the three parts and ask, ' Whose is this?' The man who was facing the other way would say, 'Company A, B, or C.' Then the man who had charge of each company took its portion and divided it in the same way to the four squads, into which the company was divided. The man in charge of each squad would take its portion and cut it into as many pieces as he had men in his squad, and distribute them in the same way as before described, while the men would watch the operation with a hungry, anxious look upon their faces, as they realized the hopelessness of being able to satisfy their hunger with the small amount of food given them for a whole day, as it was not half enough for a single meal. Perhaps there would be no better time to tell of what our rations consisted than now. When I first entered Andersonville, the prison was in charge of a lieutenant of the army, and he allowed us one pint of meal per day. It was cob and corn ground together, and a piece of bacon about one inch square. About the twentieth of April, Wirtz took command of the stockade, and he at once reduced our daily allowance of food to two thirds of a pint of meal, and a very small piece of bacon. I wish to say here that the bacon was that which had been condemned as unfit for their soldiers, so it was sent to feed the prisoners with. Most of the time it was alive with maggots. The way of cooking the food was by taking the meat on a tin plate and setting the plate on a fire, then the maggots would crawl out and we could throw them away; then, after mixing the meal with water, fry it in cakes. Of course I could not do this, so my comrades would do it for me, for which I was truly thankful,

for without this and other kind favors, the writer would not have lived to write this story. For some time after I entered the prison, the only water that we had to drink was from a brook which ran through the middle of the stockade. This brook came through two rebel regimental camps, and all the slush and grease trom their cook-houses was thrown into it, so that when we drank from it our mouths would feel and taste as if we had been eating fat meat. After a time they allowed us to dig wells, and many availed themselves of the privilege and got pure water.

"Sometime in June, during a severe rain-storm, a spring broke out near one side of the prison, and the men named it "Godsend Spring," which indeed it was to all the prisoners confined there. Andersonville was a parallelogram in shape and contained twenty-five to thirty acres, but was afterwards enlarged by about twelve more. It was surrounded by a fence twenty feet high, made of square logs set two inches apart, the lower ends sunk into the ground about three feet, and the top ends pointed. The guards were outside this fence on the ground. The dead line was a fence two and a half feet high, made by driving posts

into the ground a rod apart and nailing a two or three inch scantling on top. This was about twenty feet inside the stockade. The object of this dead line was to prevent the prisoners from digging the stockade down, as nearly every morning the guards would find from one to six posts and some of the prisoners gone. They were hunted with bloodhounds and almost always found and brought back; only one or two succeeded in reaching our Union lines, while one poor fellow who failed to climb a tree was almost torn to pieces by the bloodhounds. No blame can be attached to the rebels for building the dead line,

but they were to blame for allowing the abuse of prisoners by the guards. The orders were for the guard to shoot any prisoners who crossed the dead line, and as a reward for so doing he was given thirty days' furlough and the first commission vacant in his regiment, and as their story would be believed before ours, they did not wait for a prisoner to cross the line before they shot him. I will give two examples; one was a poor sick man unable to

eat the rations given him, and so weak that he could only crawl on his hands and knees, seeing a piece of hard-tack near the dead line which some new prisoner had shaken from his haversack, he tried to get it, but he was so weak that when he lifted his hand to pick it up, he tipped forward. The guard, who had been watching him closely, instantly fired, sending a ball through his head, for which the guard got his reward, both a furlough and a commission

for killing a Yankee. The other was a case of a prisoner who stepped up to the dead line and rested his elbow on it for a moment, but seeing that the guard was going to shoot, he jumped back and stepped quickly to where some men were standing, but the guard fired at him and missed him, but he hit one of the others, breaking his leg, the ball glanced and killed a man who was asleep a few feet away. Other cases similar to these might be told, but these are enough to show the abuse of the dead line, and the way they were sustained by the officer in charge in wickedly shooting men without a cause. Most

of the prisoners had shelters made of pine boughs, in which to sleep, and the floors were carpeted with pine needles. These were very comfortable and afforded a good deal of protection from the sun and rain. One was built for the writer of this, just large enough for two, and a member of the Sixth Illinois Cavahy, who had just come into the stockade, was allowed to share it with me on condition that he assist me in caring for myself. He did

as he agreed to, and was a great help and comfort to me. The way the pine boughs were obtained was in the following manner: Four men from each company were sent out into the woods every morning to get wood with which to do cooking; as one of them could bring all the wood required, the others would bring pine boughs to build the shelters. Owing to the hick of means to keep clean, the prisoners had become very filthy, and our clothing had become intested with vermin in the shape of body lice, and the morning hour was devoted to hunting and destroying these pests. It was a novel scene to see the men take off one garment after another, and hunt for these pests. Luckily, or unluckily, our wardrobe was very scant: my own consisted of about two thirds of a blouse, and two thirds of a pair of pants. I had neither shirt, stockings, shoes, or hat. The misery caused by these little pests cannot be described, but some idea may be formed from the fact that while it was more than three months after I letf Andersonville before I reached home, yet my back, the entire length of the spine, was one complete sore from being bitten by those pests.

"Sometime in the latter part of May, Captain Wirtz built a cook-house and commenced issuing cooked rations to one half the prisorers and raw rations to the other hall, so they got cooked and raw rations on alternate weeks. The cooked rations consisted of a piece of corn bread about one inch in thickness, two inches wide, and four inches long, with the usual piece of bacon. When it was my turn to draw raw rations, I would exchange with someone who had cooked rations, as it had become more diflicult to get wood with which to do the cooking. Occasionally in place of the bread and bacon, we were gixen a pint of hasty pudding, at other times a pint of boiled rice: this rice was olten wormy and vou had to look closely in order to see which was a worm or kernel of rice: at other times they would give us a pint of cow peas cooked with the stems and leaves just as thev were taken iVom the threshing floor: once I had these stems and leaves taken out from my portion, leaving about three tablespoonluls of beans. These rations were given once in twenty-four hours. Should any prisoner escape during the night, the rations were cut off from that half of the stockade to which he belonged for twenty-four hours. The prisoners were obliged to fall into line every morning and were counted by Captain Wirtz and his aids.

"Along in May, prisoners were brought in from New York regiments, consisting of bounty jumpers and the rougher element from that great city, who formed themselves into raiding parties; and whenever they saw any of the prisoners with money or watches, or anything which they desired, they would make a raid upon them in the night and forcibly take it from them. These acts of lawlessness were usually accompanied by more or less disturbance, which endangered the peace and safety of the rest of the prisoners, as orders had been issued by the general commanding the guard, that if any tumult occurred in the stockade, which did not immediately cease, the three batteries of artillery which commanded the stockade would open fire and shell it until every man was killed. In view of this danger, the better class of the prisoners went to Captain Wirtz and stated the cause of disturbance to him, and handed him a list of over one

hundred names of those who had been disturbing the quiet of the prison, and asked him to arrest them and hold them outside the stockade while they themselves would form a court consisting of judge, jury, and lawyer, who would try the offenders. This he consented to do, and accordingly each one received a fair trial. About fifteen were sentenced to wear a ball and chain for three months; six were sentenced to be hung, the rest were allowed to return to the stockade with the understanding that if caught in any other scrapes they would be severely dealt with without any further trial.

"On July 10, requisition having been made for lumber with which to build sinks, Wirtz furnished the right kind of lumber as he knew the object for which it would be used, and the prisoners immediately commenced the erection of a gallows. On the following morning, July 11, Wirtz brought the six prisoners who had been sentenced to be hung inside the stockade and delivered them up to the men who had formed the court which had tried and sentenced them. One of the prisoners broke away, saying that they shouldn't hang him, but by the time the others had been put upon the scaffold and the rope put about their necks, he was back and the rope around his neck also. The prisoners were asked if they had anything to say for themselves why they should not be hung; only one said

anything, he declared his innocence of the crime for which he had been tried, but confessed to having committed murder sometime previous, so they concluded to hang him for that. After prayer by the chaplain, the spring was touched and the six guilty men received their just deserts. The rope of one broke, and he fell to the ground with the cry, 'For God's sake, save me, save me.' He was immediately seized, the drop put into place, and the rope tied and again swung off, this time successfully. From this time forward the stockade was as quiet as a Sabbath morning.

"Sometime in the early part of July, the surgeons appeared to become very solicitous for our welfare, and desired the prisoners to be vaccinated, as they feared small-pox would break out in the prison. A number of the prisoners consented; this was a fatal mistake, for when the virus began to work gangrene would get into the sore and eat the flesh from the muscles and veins and bone of the arm, necessitating the amputation of the arm, which would invariably be followed by death. Of all the cases of amputation which came under my observation, but one survived.

"During the months of June, July, and August, the death-rate reached its highest figures, averaging over one thousand per month. Those who died during the day were brought to the gate and laid side by side, like sticks of cord wood; those who died during the night remained where they were until morning, when they were brought and laid beside their fellows, when the dead cart would arrive and convey them to their burial place. Soon after the war ceased the government had a cemetery made at Andersonville, in which those who died in prison were buried, and men are constantly employed by the government to care for this cemetery. Flowers are grown upon the graves and the walks and everything about the cemetery are kept in perfect order, while from a flagstaff from

sunrise to sunset the flag which these men loved so well in life, floats over their silent graves!

"On the first of June, it commenced to rain, and rained every day for twenty-one days, and about this time three hundred prisoners were brought in who could find but little or no shelter, and were obliged to lie upon the wet ground nights; in consequence of this, at the end of three months only thirty-four of the three hundred were left to tell the story of their suffering.

"In the latter part of August, I began to be troubled with scurvy, which first showed itself in my gums, then in the cords of my legs, which began to swell and contract, my legs being bent back at the knees so that my heels almost touched my hips, and I was unable to take a single step.

"About the first of September, the authorities began to remove the prisoners from Andersonville, as they thought General Sherman was going to come down there to liberate us. In the middle of September, orders were given to my detachment to be ready to march at a moment's notice, and that all persons who could not take care of themselves must be left behind in the hospital; as I knew this was almost certain death, I determined to make every possible effort to get away with my detachment; this seemed hopeless, as I could neither see nor take a single step. About 6 o'clock in the evening, a friend procured me some cold water with which I bathed my knees freely, rubbing the cords vigorously, which so relieved me that I was able to walk for half an hour. I then gave them another good bathing, and, after eating a few mouthfuls of food which I had left, I lay down for the night. The following morning as I had no breakfast to get, I gave my knees another good bathing and rubbing, and as I was on the point of again practicing, the order came for our detachment to fall in, which was very fortunate for me, as it found me in a good condition for marching. When the order was given to march, they told us to lock arms two by two; this gave me a guide and so enabled me to get by those who were inspecting us as we marched out, and I can assure you I was glad to bid adieu to that prison of horrors, Andersonville.

"When we arrived within one hundred yards of the depot, the column was halted, and as my limbs were paining me I sat down upon the ground; this was a mistake, for my legs resumed their old position, and when the column moved I was unable to take a step. Two of my comrades said I shouldn't be left behind, and seizing me under each arm, helped me along, dragging one foot after the other on the n-round; as we had to cross three railroad tracks, this was a very painful experience. I was placed in a box car with other prisoners, and soon the train started for Savannah, Ga., where we remained thirty-six hours, being kindly treated and well fed. We were then put aboard a freight train and sent to Charleston, S. C. On our arrival at that place, I was lifted from the car and placed upon the ground. Soon two of my comrades came running along and stopped to speak to me. I asked them where they were going ; they said we were close to a river and they were going to take a bath, as they had been unable to do so for more than six months. As I expressed a desire to enjoy the same blessing, they promised as soon as they had finished their bath to come and give me one also, which they did, much to my comfort and benefit.

"As they were taking me into the water, a rebel soldier (who had been a prisoner at the North and been exchanged) came along, and asked what was being done, and what was the matter with me. Upon being told, he handed them a towel and some soap, saying, 'give him a good wash,' and immediately went away. As they were bringing me out of the water, after my bath, the soldier returned, and gave me a pair of cotton pants and a shirt, saying they were much better than the rags which I had been wearing. After I was dressed, he gave me a tendollar bill, saying I would find a use for it before I got home. Of course I thanked him heartily for his kindness, and have always regretted I did not learn his name. My comrades then carried me and left me near the railroad track where they had found me. Soon I, with others who could not walk, was put into an open wagon, and driven through the city to the other side of it, where we were to remain for a while; when passing a bakery in the city, the same soldier who had befriended me came out with three loaves of bread, and throwing them into the wagon, said they were for the blind man. I got one of them, the other two were divided among the rest of the team.

"After I had been in Charleston a few days, I was taken sick with chronic diarrhoea, and I knew unless I could get help soon, I couldn't stand it but a short time; but fortunately for me, three or four days later I was admitted to a hospital, where I received good medical attendance, proper food, and had a good bed, and the greater part of the time during four days and nights, I enjoyed a restful sleep. In about two weeks I was so far recovered as to be able to walk. As fast as the prisoners got well at the hospital, they were sent to Florence or Columbia, S. C.

"When I was nearly recovered, I asked the doctor if he was going to send me to the stockade as soon as I was able to go. He said he would be obliged to do so, as men were dying for want of care which could be given them in the hospital. I told him I should certainly die if I was again sent to the stockade, and it would be just as well for him to save my life as any, and a great deal better for me. I settled it in my own mind that if it could possibly be helped, I would not again go to the stockade.

"When I was pronounced well, I was placed on full diet, and could get all the food I wanted; as we always knew a day or two before a squad was to leave, I would secrete a part of my food, and the night before a squad was to leave, I would eat so much as to make myself sick and unfit to be sent away. This I did at two different times, and the doctor understood my condition and told me not to do it any more, as he had decided to keep me as long as anyone stayed; and I remained in Charleston imtil I was exchanged.

"On the morning of November 28, a messenger came from the provost marshal's office at Charleston, the messenger was a prisoner like myself, and he told me that we were going to be exchanged, and ambulances would arrive in about an hour to carry us to the city. This seemed too good to be true, but the ambulances came and took the worst cases and started for the city. At the provost marshal's office we were met with the intelligence that the Yankees had captured the railroad between that city and Savannah, and we must return to the hospital. This news was soon contradicted, however, and we started for the

depot, and were put into box cars on a freight train and started for Savannah, where we were to be paroled; and although it was just ninety miles it took the train nineteen hours to reach the city. They were so afraid the Yankees would capture the train that they would stop every two or three miles to telegraph to see if the road was clear. We left Charleston at 10 p. m., the 2Sth, and reached Savannah at 5 p. m., the 29th.

"On the morning of the 30th, we were taken on one of their steamers down the harbor and transferred to one of the United States vessels, and it would be hard to find a happier set of men than we were when we found ourselves once more under the protection of the stars and stripes.

"After we had been on board our vessel about one hour, they brought us each one hard-tack and a piece of fat pork about an inch square; this was the sweetest and best meal I think I ever enjoyed in my life. The vessel we were on carried us to Hilton Head, S. C, where we were transferred to the steamer 'George Leary,' which had been fitted up for our use to convey us to Annapolis, Md., where we arrived December 4. Here we received new clothing and the best of care, and were paid our back ration and clothing money.

"I remained at that place two weeks, and having received a furlough I went to Philadelphia, where I remained three days. I then started for New Hampshire,

and arrived safely home at 4 o'clock in the afternoon of the 23d of December, just three years, one month, and twenty-four days from the time I enlisted. I shall not attempt to describe my feelings on reaching home, for it would be impossible to do so.

"For want of space I have omitted a great many particulars with regard to the horrors of Andersonville, as well as a great many other incidents of prison life which would no doubt have been interesting and instructive, but the foregoing narrative will suffice to give a faint idea of the sufferings endured by prisoners of war, while in the hands of the Confederate authorities."

Return to the 7th New Hampshire Infantry page.

Battle of Olustee home page