...The Olustee rout ended any concerns the Andersonville [Confederate prisoner of war camp in Georgia] staff may have entertained about trouble from the south."

[Later at Andersonville: pages 41-42]

"...One of the first carloads of Olustee prisoners included Archibald Bogle, the major of the 1st North Carolina Colored Infantry. Judging from a camp order issued the next day prohibiting the practice, large numbers of off-duty soldiers must have crowded the railroad platform to see the black Yankees and their leader. Bogle's chest and leg wounds had hardly begin to heal, so his subordinates bore him on a litter. Camp Sumter [Andersonville prison] had been intended for enlisted men, but the Confederates refused to acknowledge Bogle as an officer, and he had been sent from Tallahassee to the stockade deliberately. Colonel Persons treated him decently enough, but the medical staff would not attend to him, perhaps hoping he would die of his wounds. He survived, however, though for many weeks he seemed not to imporve. Later, when he could get about on crutches, swung himself over to the hospital, which had grown by several more tents and flies. A hospital steward - a prisoner like himself - bandaged his leg, but Surgeon White recognized the major by his shoulder straps and told the steward to stop working on him and send him back outside "with his niggers." Bogle remained at Andersonville though most of 1864, despite Henry Wirz's personal efforts to have him exchanged or sent to an officers prison.

In his own words...

"On the 14th of March, 1864, I came to the stockade feeling very faint. I heard there was a hospital inside the stockade, and I got some men to help me up there. I was on crutches at the time. I went in, and one of our own men who was acting hospital steward, commenced to bind up my leg, and was binding it when Surgeon White came in and ordered him to desist, saying at the same time, 'Send him out there with his niggers;' or something to that effect, and using an oath at the same time. I said nothing , but merely looked at him. The hospital steward finished the dressing of my leg, and it was cared for by our men afterward. I was in full uniform. ... While I was there I demanded to have my rank recognized. I made several demands. I was used in every respect the same as private soldiers, only worse. ... When I got to Millen an officer came to me and got my name, rank, and regiment. The officer commanding at Millen, Captain Bowles, put me in the stockade again and refused to put my name on the register, saying at the same time that I should never be exchanged. I left Andersonville on the 18th of November, I believe." - from A Brave Black Regiment

Major Bogle reached Camp Sumter on March 14, and shortly afterward a civilian arrived among some other Olustee prisoners. David A. Cable, who had been a captain in a ninety-day Ohio regiment in 1861, had apparently dropped out of the conflict because of dissatisfaction with the political turn it had taken. Somehow he attached himself to the Federal army that penetrated Florida, and when he fell into Southern hands he introduced himself as what might have been called a minister extraordinary - very extraordinary. He said he had come representing Northern peace men who wished to work with the Confederates to see Lincoln defeated in the November election. From the Andersonville stockade he wrote the Confederate vice-president Alexander Stephens, to propose a meeting; Stephens asked President Davis to grant Cable a parole for that purpose, but David and Stephens did not get on well and the arrangement was never made. The gate that closed behind Mr. Cable would not reopen for him while he lived.

Other Olustee contingents straggled in through the last of March. On the 22nd many of the 7th New Hampshire arrived, and toward the end of the month an Italian Swiss named Frederick Guscetti came in with his comrades of the 47th New York. Guscetti, like most of the Olustee wounded, had to be carried from the depot to the stockade in a wagon. Like every new trainload from Tallahassee, this one contained a few more black men: the Americus [newspaper] editor counted eleven on them on Sunday, March 27. Colonel Persons inquired what to do with them, in light of the president's proclamation on that subject, but General Winder told him to hold them as ordinary prisoners of war until the questions was resolved at a higher level. Persons just marched them into the stockade, where they congregated in their own little encampment near the south gate - ignored by everyone, including the doctors.

[Still at Andersonville: page 112]

"...A Catholic priest from Macon, exaggerated only slightly when he said that the stockade housed every nationality in the world. Captain Wirz, who was trilingual himself, employed a number of nonnative prisoners in and around his office to translate for those who could not speak English, including the Italian, Guscetti [47th New York], who spoke seven European languages, and whom Wirz assigned to the hospital as an interpreter for the surgeons.

"...Several other officers [besides Union surgeons] camped inside with their men, notably Major Bogle, and the assistant secretary of the Confederate War Department authorized the commander of the Macon officers' prison to send a lieutenant of the 35th U.S. Colored Troops to Andersonville to keep Bogle company. Most of the other officers who found themselves behind the palisade still wore sergeant's stripes, either because their commissions had arrived at regimental headquarters after they were captured or because they had not yet been mustered in..."

[Evacuating Andersonville: page 221-222]

"...but aside from the patients in the hospital [numbering well over five hundred] barely two hundred Federals remained at Andersonville, and four of them promptly walked away. These two hundred apparently consisted of detailed clerks, carpenters, nurses and blacks. Wirz retained the black prisoners as long as he could, using them for the graveyard crew and keeping them, per order of the secretary of war, for identification by professed owners of runaway slaves. The major of the 1st North Carolina Colored Infantry, Archibald Bogle, still remained with his men.

Bogle's days at Andersonville were numbered, however. Sherman's blue behemoth had begun to stir in Atlanta... and Camp Sumter authorities hurried to rid themselves of still more Federals.

"... Three days after the trainload of sick departed, Henry Wirz forwarded eight more Yankees to Millen [another prisoner of war camp] under special escort. Seven of them were enlisted men... The eighth Federal was Major Bogle, whom Wirz sent ahead for a personal interview with General Winder; after eight months at Andersonville, Bogle hoped Southern animosity toward Colored Troops officers had abated. Wirz obliged him with a letter of introduction to Winder, explaining that the prisoner wished to be recognized and exchanged as an officer. He put all eight Yankees aboard the regular train with a couple of guards... neither the letter nor the special escort brought the major his freedom. Wirz's counterpart at Camp Lawton simple threw Bogle into a larger and somewhat-less-defiled stockade."

More on Major Archibald Bogle...

According to official records, Bogle was confined at Andersonville for nine months and paroled at Wilmington, North Carolina in March 1865 where he came through the lines. As of 18 March, he was brevetted a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Volunteers. He was finally discharged in April 1866, at Charleston, South Carolina. After a short period home in Massachusetts, Major Bogle continued service in the Army (but at a lesser rank) after the war and was finally discharged in 1871. After that, and until 1889, he spent his time "on the frontier" before going to California, according to his wife.

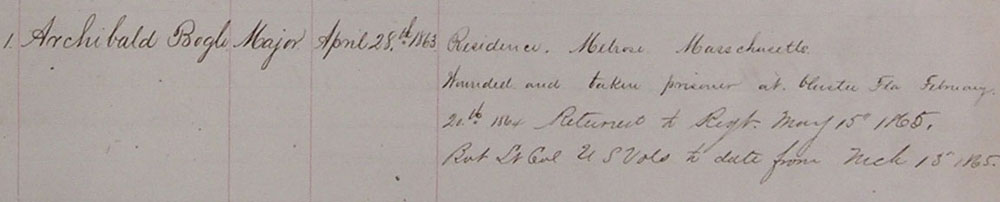

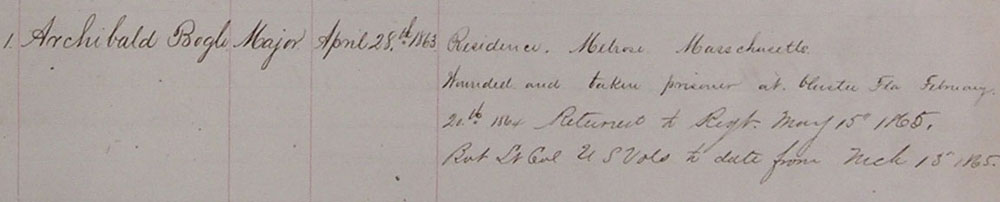

Text: "Archibald Bogle; Major; April 28th 1863; Residence, Melrose, Masschusetts (sic); Wounded and taken prisioner at Olustee, Fla, February 20th 1864; Returned to Regt. May 15th 1865; Bev Lt Col U S Vols to date from Mch 18th 1865."

Records from the Adjutant General's Office state that Archibald Bogle was appointed as a first lieutenant in the 39th Infantry on May 21, 1867. He joined his company July 1867 and served with it:

- at New Orleans, LA to January 1868

- at Fort Pike, LA to March 1869.

He was transferred to the 25th Infantry on April 20, 1869 and served with it:

- at Baton Rouge, LA, until May ?

- at Ship Island, MS until July 5. 1869

- on leave until August 9, 1869

- at Ship Island, MS until December 20, 1869

- on leave until January 13, 1870

- at Ship Island, MS until April 5, 1870

- at Jackson Barracks, LA until May 1870

- enroute to Texas until June 16, 1870

- on regimental recruiting service in Memphis, TN until April 4, 1871

- enroute to and with company at Duncan, TX until November 28, 1871

- under arrest August 30, to November 28, 1871

- left for Jackson Barracks, LA, but records showed he never joined there.

- dismissed from service on December 20, 1871.

General Court Martial Orders No. 29, issued from the War Department Adjutant General's Office in Washington on December 20, 1871 state that a court martial was convened for 1st Lt. Archibald Bogle on October 7, 1871 at Fort Duncan, Texas. The president of the court was Colonel Abner Doubleday, 24th Infantry. Bogle was charged with two counts:

- "Conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman" in that on August 27, 1871, at Fort Duncan, Texas, he was accused of going to the private quarters of assistant surgeon Alfred C. Girard and shot a pistol at that officer who was seated at a table with his family.

- "Assault with intent to kill, to the prejudice of good order and military discipline" under the same circumstances described above.

Bogle pleaded "not guilty" to both charges, but was found guilty by the court on both counts. He was sentenced "To be discharged from the service of the United States, and then to be confined to such penitentiary as may be designated by the proper authority for the period of two (2) years." However, "All the members of the court, except one, unite in a recommendation that 'in consideration of the previous good character and excellent record of the accused during the late rebellion, so much of the sentence as relates to confinement in a penitentiary be remitted.'"

The War Department approved this recommendation, in light of Archibald Bogle's previous service and imprisonment at Andersonville and because not only were assistant surgeon Girard and his family not injured by Bogle's attack, but return fire from assistant surgeon Girand actually wounded Lt. Bogle.

Letter Detailing the "Death" of Major Bogle and What Happened to Him After the War

The above information provided by James G. Bogle, Jr, of South Carolina.

Other Letters from Olustee

Battle of Olustee home page

http://battleofolustee.org/